AGOA: The US-Africa trade program

The cornerstone of U.S. economic relations with sub-Saharan Africa since 2000 has been the African Growth and Opportunity Act, or AGOA. The program offers more than three dozen participants preferential access to U.S. markets by eliminating import tariffs.

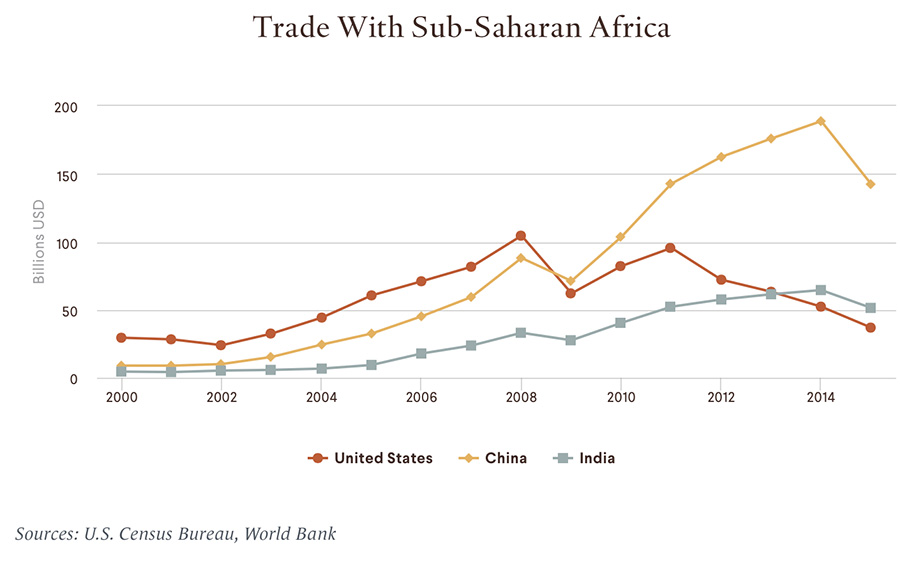

Policymakers hoped that AGOA, as the primary U.S. trade policy for the region, would foster economic and political development in Africa. However, the outsized role of oil and apparel in African export growth has raised questions about whether AGOA can diversify the region’s economies and increase its competitiveness in global markets. Meanwhile, U.S. trade with AGOA’s participants has dropped since its 2008 peak almost to its pre-AGOA total, while African trade relationships with other countries, particularly China, have expanded.

Why was AGOA created?

AGOA is a trade preference program established in 2000 as part of broader legislation to strengthen U.S. trade ties with Africa and the Caribbean enacted by President Bill Clinton. The act is unilateral, meaning that it does not require African countries to lower their own barriers to U.S. goods, though it encourages them to do so. President Clinton saw the policy as a way to boost growth and bolster democratic ideals across the continent. He also said that it would strengthen the U.S. economy by opening markets with “hundreds of millions of potential consumers” to American producers.

The act is an extension of a U.S. trade preference system introduced in 1974 that allows more than one hundred countries, mostly in the developing world, to export many of their goods to the United States duty-free. AGOA goes even further, offering this access to more than six thousand products from its thirty-eight current participants. It also mandates the executive branch to increase U.S. development assistance to sub-Saharan African countries in areas including agriculture and HIV/AIDS prevention. It was set to expire in 2008, but has since been renewed four times.

Which countries take part in it?

Only sub-Saharan African countries are eligible to be beneficiaries of AGOA, and the legislation outlines requirements candidates must fulfill, such as upholding the rule of law and human rights and liberalizing their economies. However, U.S. presidents may disqualify countries at their discretion, and have done so, for reasons such as rights violations or protectionist policies. Participants graduate out of AGOA if per capita gross national income reaches $12,235, the World Bank's lower limit for high-income countries.

Of the forty-nine potential beneficiaries in the region, thirty-eight countries currently take part. Ten are currently suspended: Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Gambia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe. The Seychelles graduated out of the program at the start of 2017.

How has the program fared?

AGOA received strong bipartisan support early on, with policymakers and trade officials pointing to a spike in U.S. imports of African goods as proof of its success: In the decade after the program began, exports from AGOA countries to the United States nearly tripled, rising from $22 billion to $61 billion. In 2010 Rosa Whitaker, a former assistant U.S. trade representative for Africa, called AGOA a “phenomenal success,” saying it had created more than three hundred thousand jobs on the continent, while the nonprofit African Coalition for Trade estimated in 2012 that up to 1.3 million jobs [PDF] were created indirectly.

Some analysts say the program has also helped several African countries diversify their economies. For example, South Africa ramped up its automotive exports to the United States from $151 million in 2000 to a high of $2.2 billion in 2013. Apparel production also spiked, particularly in East Africa. The most AGOA-related jobs were generated in this sector, according to the Brookings Institution.

However, some experts say U.S.-Africa trade relations remain underdeveloped. After an initial jump, for instance, exports have fallen below their 2000 level. Diversification has also lagged, as oil continues to dominate exports from participants, consistently making up at least two-thirds of AGOA trade since 2001. Three countries—Nigeria, South Africa, and Angola—contribute the vast majority of total exports. Additionally, just 1 percent of imports to the United States in 2015 came from sub-Saharan Africa, a 50 percent decrease from 2000; by comparison, the region contributed about 4 percent of China’s imports and 8 percent of the European Union’s.

Why has the program been criticized?

Enthusiasm for AGOA among U.S. policymakers has flagged in recent years, with some analysts pointing out that AGOA participants’ exports have decreased, in 2016 dropping below their level when the program started. There are also concerns about Africa’s continued dependence on low-value-added products and natural resources; beneficiaries export few of the higher-value manufactured products that the legislation hoped to spur.

CFR’s Michael Froman, the U.S. trade representative under President Barack Obama, suggested in 2014 that obstacles including corruption and poor infrastructure were hindering the competitiveness of African producers and limiting the program’s success. Trade expert Kim Elliott argues that the United States has failed to provide sufficient financial assistance to help African economies upgrade their competitiveness.

Other analysts say that the United States should push for more private-sector investment to take advantage of the region’s economic growth, which was higher than the global average over the fifteen years after AGOA was implemented. Some, like the Brookings Institution’s Witney Schneidman and Moyombuya Ngubula, suggest a transition toward two-way trade policies, since at its inception AGOA was widely viewed as a first step toward permanent free trade agreements (FTAs). However, Washington has not concluded any FTAs with sub-Saharan African countries. While it did hold negotiations with South Africa, they failed in 2006, primarily due to disagreements over intellectual property rights and foreign investment rules.

How have other countries approached trade in Africa?

Sino-African trade has soared since 2000, with China surpassing the United States as Africa’s largest trade partner in 2009. Beijing maintains special trade and economic cooperation zones in several sub-Saharan countries and has provided more than $100 billion in foreign direct investment and development loans to the region. Analysts have raised concerns, however, over the high levels of debt that some African countries have taken on as the result of Chinese financing, which, they say, could potentially spark crises.

The European Union has signed economic agreements with regional blocs in western, eastern, and southern Africa in which both sides offer preferential treatment on tariffs for certain goods. It has also established interim trade partnerships with countries including Cameroon, Madagascar, and Zimbabwe, and negotiations of other regional deals are underway.

India has expanded its presence in the region as well; its trade with the region saw a fivefold increase from 2000 to 2015, reaching $51 billion, alongside surges in private investment in telecommunications, information technology, and energy.

What is the future of AGOA?

AGOA was last renewed in 2015 and is set to expire in 2025, though President Donald J. Trump could ask Congress to repeal the legislation. CFR’s John Campbell and Allen Grane say that while this is unlikely, the administration could threaten to cancel the program as a negotiating tactic to secure greater access for American goods and services to the African market.

""The best hope for AGOA is that it will be allowed to remain in place with declining support until it expires."" - Johnnie Carson, Former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs

Other experts say the Trump administration, in keeping with its stated preference for bilateral trade agreements, believes it can achieve better terms by pushing for two-way deals instead of regional pacts. Officials have not yet indicated any plans to change current policy, though Peter Barlerin, then the deputy assistant secretary of state for African affairs, said during the 2017 AGOA forum that it is “up to the beneficiary countries to enhance their business climates.”

Meanwhile, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative is considering disqualifying Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda from the program over their plans to introduce some protectionist policies to boost their domestic apparel manufacturing. That has left some experts less than optimistic about the program’s future. As Johnnie Carson, former assistant secretary of state for African affairs, has written, “The best hope for AGOA is that it will be allowed to remain in place with declining support until it expires.”