'Does AGOA unfairly benefit Chinese firms?'

On the face of it, this multi-national system appears to be a win-win – evidence of trained African employees entering the global value chain, funded by Chinese partners and ready to take full advantage of American trading privileges. Yet not all Africans see it this way. As the first black South African to lead his country’s Reserve Bank, and a director of the $50bn New Development Bank in Shanghai, Tito Mboweni has long earned a reputation for robust and unfiltered opinions.

In November, Mboweni turned his ire on the cornerstone of this export system – an American trade act designed to benefit African manufacturers.

“Chinese entrepreneurs benefited from the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) […] very few African entrepreneurs benefited. For our governments to build many shell factories and literally hand them over to Chinese entrepreneurs is actually an embarrassment for all of us,” he said.

For some, Mboweni’s trenchant critique was bizarre. AGOA, signed into law by the Clinton administration in 2000, was designed to provide African manufacturers with tariff-free access to the US market in an attempt to bolster flagging trade with the continent. Defenders argue that the legislation has proved a dynamic employment vehicle in signatory countries, driving the creation of as many as 350,000 direct jobs by removing tariffs on some 6,500 products including vehicles, garments and metalwork.

The Obama administration seemed to agree – in 2015, it signed a 10-year extension to the act in a move welcomed by African governments and manufacturing associations.

“The feeling was that it doesn’t matter where capital comes from as long as jobs are being created and labour conditions good, and the people and governments benefit […] Whether it’s a Chinese, Indian, or Turkish company is not the prime consideration,” says Witney Schneidman, senior international advisor for Africa at law firm Covington & Burling, who was involved in the passage of the act.

Yet for its detractors, AGOA has had a far more pernicious effect, allowing Chinese and Taiwanese firms to colonise African manufacturing space and curtail indigenous businesses in a cynical bid to access the lucrative US market. With Donald Trump’s presidency dedicated to recasting trading relations – and keen to propagate the idea that China is taking advantage of the US – the debate over who benefits from AGOA could play a key role in US–Africa relations in the years ahead.

Fact or fiction?

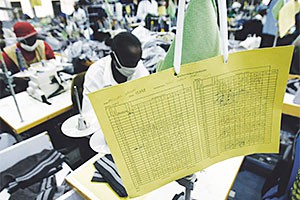

From Huajian, the footwear firm employing around 3,500 in Ethiopia’s “Shoe City”, to the expansion of C&H Garments in Rwanda, Chinese influence on Africa’s clothing sector is anything but secretive. Yet while savvy Chinese firms have long opened their doors to the media, promoting their roles in job creation and skills transfer, Mboweni’s speech was not the first time that critics have questioned whether Chinese firms are really in it for Africa’s benefit.

In 2012, three researchers at the University of Oxford’s Centre for the Study of African Economies, Lorenzo Rotunno, Pierre-Louis Vézina and Zheng Wang, delivered a paper investigating whether Chinese manufacturers were using Africa as a trade corridor to access the US market. They discovered that a combination of restrictive US quotas on Chinese apparel imports and the preferential treatment handed to African manufacturers gave Chinese firms an incentive to route their trade through the continent, even while providing very little work to African employees.

“What we showed in our article in the Journal of Development Economics is that there is some statistical evidence that AGOA has allowed Chinese businesses to use African countries as a trade corridor to reach the US,” says Vézina. “This was possible thanks to the absence of rules of origin, meaning that AGOA countries were allowed to source as much garment as they wished from China and re-export to the US.”

The report concluded that in many cases, African involvement was limited to little more than final assembly of almost finished products. Yet the report also argued that the 2005 collapse of the Multi-Fibre Agreement – an international system that had imposed quotas on mainland Chinese exporters – removed the incentive to continue with this backdoor African operation.

By 2013, according to Tang Xiaoyang, a professor at Tsinghua University, Chinese investment in southern Africa’s apparel sector was at a third of peak levels, the result of the collapse of the MFA, rising labour costs, a skills deficit, and the cancellation of incentives by African governments.

Low-cost southeast Asian firms stepped into the breach – a 2016 report from the Office of the US Trade Representative found that while exports from Africa to the United States had increased from some $600m in 1999 to almost $1bn in 2015, exports from Vietnam increased over the same period from virtually zero to $10.7bn.

Job creation?

Against the apparent backdrop of limited Chinese interest in African textile manufacturing, the claim that the remaining Chinese manufacturers have unduly benefited from AGOA legislation has proved highly contentious.

“I think the criticism is a red herring to be honest,” says Schneidman. “Chinese companies have been at the forefront of helping to expand the production and manufacturing of apparel products in Africa […] This is really about Africa benefiting from jobs created, labour conditions being respected and taxes paid.”

Helen Hai, chief executive of the Made in Africa Initiative, a co-founder of C&H Garments and a former executive at Huajian, says that it is foreign bulk buyers, rather than African or Chinese manufacturers, that benefit the most from the tariff reductions of AGOA. She adds that rather than taking advantage of their African hosts, committed Chinese firms are bringing manufacturing expertise that the continent previously lacked.

It is this continuing knowledge deficit, rather than an overbearing Chinese presence, which is preventing Africans from accessing AGOA privileges, she argues. “The first question is why Africa hasn’t benefited from AGOA. The answer is that the manufacturing knowledge does not exist. If you are seeing Chinese and other Asian manufacturers taking advantage of AGOA, that’s great news. It means manufacturing know-how is being passed to the continent.”

Hai points out that while Chinese firms are initially attracted to cheaper African labour, they soon prize quality control and staff expertise. She argues that African employees trained in Chinese factories frequently move on to local competitors for higher wages – a process that she says spreads knowledge and speeds the development of manufacturing clusters like Shoe City.

Without Chinese manufacturers, she argues, the process collapses. “The reason China is able to have scalable manufacturing skills is because they created a cluster. You get economies of scale. That’s the same thing in Africa – I wanted Ethiopia to become the manufacturing centre of the world for shoes.”

If blue-collar wages continue to rise in China, analysts believe that Chinese manufacturers will again look to Africa as a source of affordable labour. Hai says that rather than obsess over the division of AGOA privileges, African countries should be preparing to compete for this influx of investment before it heads to southeast Asia.

Yet while AGOA defenders bemoan the criticism of Chinese and Taiwanese firms in Africa, questions remain over whether these textile firms are serious about promoting African staff. While higher profile firms boast affirmative policies, the sector is not immune to a wider reluctance among Chinese investors to hand management roles to Africans.

Until that happens, the argument that Chinese, rather than Africans, benefit from AGOA is always likely to gain some traction. “This is one of the challenges to Chinese companies – the fact that we don’t see African CEOs or chairmen of Chinese companies in Africa. That’s really an issue between African governments and Chinese entrepreneurs,” says Schneidman.

Future of AGOA

While critics and defenders of AGOA appear deadlocked over the issue of Chinese influence, the election of Donald Trump has upended all assumptions about the future of the act and wider US trade policy in Africa. In a series of pointed questions to the State Department, first reported by the New York Times in January, Trump officials ask whether the US is losing out to China in Africa, and query why petroleum imports under AGOA are a “massive benefit to corrupt regimes”.

The development of this sceptical line – added to Trump’s bid to erase Chinese advantage from US trade policy – is one that worries defenders of the act. Against this hostile backdrop, tweaks may be politically necessary.

Schneidman suggests that adding clauses to AGOA to limit overbearing Chinese influence – similar to those introduced by the US Millennium Challenge Corporation limiting Chinese involvement in US-funded infrastructure projects – could defuse criticism.

Trump’s perception of China is just as important as the reality. Reform, rather than repeal, may be required if Africans – including those in Chinese factories – are to continue seeing the benefits of AGOA.